If we were to ask students and teachers the question, “What is Latin?” we would hear a multitude of adjectives related to the word: alive or (almost always) dead; useful or (mostly) useless; beautiful and ugly; ancient; interesting; boring; hard; not to mention Catholic; classist; Fascist. These are only a few adjectives, but they demonstrate how hard it is to provide a firm and impartial definition of what Latin is. Moreover, any attempt to choose an appropriate adjective often draws attention away from the main point—the quid, as Cicero would say—, namely the subject itself: Latin.

In short, Latin is a language; it is the language of the Latin people, the ancient inhabitants of Latium, or, more precisely, the Romans. All living languages change over time, and Latin is no exception. Already in ancient times—but even more so after the fall of the Roman Empire—Latin changed and, over time, neo-Latin, or the Romance languages were born.

It is a well-known fact, but one that is often forgotten, that during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance Latin, despite having become a dead language (that is to say, lacking native speakers) continued to function as a language: it was spoken, heard, read, and written. Of course, by this time Latin was learned from books, no longer at home, and students learned Latin not to go shopping, but to discuss academic subjects—the trivium and quadrivium as they were called in the Middle Ages—; but it was still Latin, that is to say, it was a language.

But what is a language? A language is nothing more than a system of sounds (spoken words and sentences) associated with things (objects, actions, thoughts, emotions) that give them meaning. The primary aspect of every language, first and foremost in a chronological sense but also in a logical one, is oral. From the very first people who lived thousands of years ago and didn’t know how to write, to illiterate people living today, to newborn babies, language is that which people say using their tongue (the organ whose articulation serves to make sounds). In Italian, and Latin, “tongue” and “language” are the same word, lingua; in English as well, as in: one’s native tongue). This point, as obvious as it seems, merits attention, especially since, according to a common way of thinking, language refers essentially to the written form. Instead, it does not. Writing, in fact—which is nothing more than an attempt to give a graphic form to the sounds we have just mentioned, and as such does not precede but follows orality—was invented only a few millennia ago, and thus quite recently in the scope of human history.

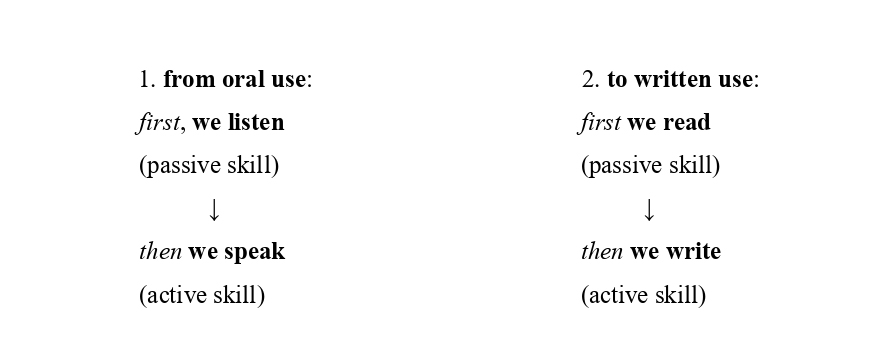

Human beings learn to emit sounds based on a shared code within a community, indeed, a language. Be it Latin or English, or any other language, what is important to highlight here is that learning any language begins naturally, and therefore, by the very nature of languages and people, it begins with listening: people listen, and by listening they learn and establish connections between the words they hear and the things those words signify. Through imitation and use they gradually learn to reproduce sounds, and they learn the language: pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. This initial oral phase of language learning, whose first stage is passive listening, is followed by the active speaking phase, which, in turn, is followed by the active writing phase.

We can illustrate what we have just said with the following scheme: This brief introduction seemed necessary because, once we have clarified the goal of our teaching (the quid), which is the Latin language, I believe we can identify and lay out the path, or rather, the method that will lead us toward our goal.

This brief introduction seemed necessary because, once we have clarified the goal of our teaching (the quid), which is the Latin language, I believe we can identify and lay out the path, or rather, the method that will lead us toward our goal.

The primary reason Latin is taught in school is for reading comprehension, and thus for a deep understanding of the classics. If this were not the case, we could read everything in translation; but if reading classical authors in their original language has been promoted in schools for more than two millennia, there must be a good reason for it, as I will demonstrate shortly.

The goal of a language teacher is to teach the language, and Latin is a language, i. e., primarily, a system of sounds, as we have said. These are sounds that have been produced, with some variations, from ancient times up to today. Not even we teachers are accustomed to hearing Latin, and yet the greater part of ancient literature was developed for oral use: the majority of plays and songs, poetry in general, and, of course, oratory.

If we want to teach Latin for the language that it is, I maintain that we should follow the scheme outlined above, adapting it to our goal, which is, as you recall, reading comprehension, or the ability to read and understand classical texts. At first glance, this could seem like a strange idea, given our collective practice of treating Latin as a dead language: one that only exists in written form and is imbued with an aura of sacrality, and which we mechanically repeat like the Roman priests did, who recited formulas that even they didn’t understand on account of their antiquity. On the other hand, though I am careful not to insist on Latin being a living language, I can’t help pointing out that it is, after all, still a language; and that it is the nature both of languages and human ways of learning to begin from orality in order to proceed to writing; to start from passive skills in order to proceed to active ones. Not because the goal is to speak and to write in Latin (which nevertheless was done for fifteen centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire), but to better understand classical literature.

Let me now provide some practical examples to better understand how to apply the principles set out above in a methodical way.

Imagine that it’s the first day of school and that our students have never studied Latin. The teacher, at a certain point, stands up and, while walking around, says: Ambulo. The teacher repeats the word (because repetita iuvant): Ambulo. It might seem puerile, but it is not, because we are creating in students a mental connection between words and things, without the need for translation. At that point the teacher turns toward a student and, adding gestures to words, says: Ambula! Again, the teacher repeats: Tu, discipule, ambula! Now both of them are walking around the classroom. Others look at them curiously, but they are listening. The teacher then says (with the aid of gestures and appropriate intonation): (Ego) ambulo, (tu) ambulas, (ille)—pointing to a third student—non ambulat. Ambulo, ambulas, non ambulat. Tu et ego, nos, ambulamus, ille non ambulat. Quis ambulat? Magister ambulat. Antonius (name of the student who is walking) quoque ambulat, Marcus (the other student) autem non ambulat. The teacher asks: Quis non ambulat? Then, turning to the students and pointing to Mark, the teacher invites them to answer by saying: Marcus. If necessary, the teacher says the words or phrases with the students. Turning to Mark, and using gestures, the teacher says: Tu quoque, Marce, ambula! At that moment the student starts walking, and the teacher says: Marcus quoque ambulat. Antonius et Marcus ambulant, vos (pointing to the rest of the class) non ambulatis. Nos ambulamus, vos non ambulatis. Vos quoque, discipuli, ambulate!

Imagine that it’s the first day of school and that our students have never studied Latin. The teacher, at a certain point, stands up and, while walking around, says: Ambulo. The teacher repeats the word (because repetita iuvant): Ambulo. It might seem puerile, but it is not, because we are creating in students a mental connection between words and things, without the need for translation. At that point the teacher turns toward a student and, adding gestures to words, says: Ambula! Again, the teacher repeats: Tu, discipule, ambula! Now both of them are walking around the classroom. Others look at them curiously, but they are listening. The teacher then says (with the aid of gestures and appropriate intonation): (Ego) ambulo, (tu) ambulas, (ille)—pointing to a third student—non ambulat. Ambulo, ambulas, non ambulat. Tu et ego, nos, ambulamus, ille non ambulat. Quis ambulat? Magister ambulat. Antonius (name of the student who is walking) quoque ambulat, Marcus (the other student) autem non ambulat. The teacher asks: Quis non ambulat? Then, turning to the students and pointing to Mark, the teacher invites them to answer by saying: Marcus. If necessary, the teacher says the words or phrases with the students. Turning to Mark, and using gestures, the teacher says: Tu quoque, Marce, ambula! At that moment the student starts walking, and the teacher says: Marcus quoque ambulat. Antonius et Marcus ambulant, vos (pointing to the rest of the class) non ambulatis. Nos ambulamus, vos non ambulatis. Vos quoque, discipuli, ambulate!

It is very important for the teacher to articulate the words well, slowly, with the right intonation, and to accompany them with gestures and actions; and to avoid the temptation to translate as soon as the students seem not to be comprehending. If necessary, the teacher may repeat the same method more times over. Subsequently, the teacher moves on to the other three conjugations—being careful to choose regular verbs: for instance, videre, audire, surgere, considere, and maybe sedere, so as to allow the students to notice the difference between the static sedere, and the active considere. After practicing this orally, the teacher may read a text with the students that contains the words and forms that the students have heard in the first lesson and, finally, he may formalize the grammar, which in these examples is the present indicative and the imperative. At that point, to complete the path we have laid out, the teacher will give the students some exercises to do, which include the use of the words, forms, and grammatical constructions that were just explained.

This path, together with what I like to call “active grammar,” could at a first glance seem easy and puerile, but in reality it requires a rigorous method, not only in order to proceed wisely and in a balanced way from the concrete to the abstract, from that which is more important to that which is less important, from more common to less common things, but also in order to avoid improper employment of the language on the part of the teacher, who often doesn’t receive appropriate training. On the other hand, our ultimate goal is not to speak Latin, and least of all to talk about our everyday life in Latin; but it is to teach the language, pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar in an organic way, in order to reach an authentic understanding of texts, without the need to pass through the act of translation. Following the order we have described, we need not sacrifice any part of language study; quite the contrary, because, on the one hand, we immerse students in the language and, on the other, we are making them aware of what they are learning, thanks to the precise formulation of words and grammatical concepts that are not abstract and devoid of any genuine communicative content, but are linked to reality, which is not only that of the classroom, but also—and most especially—that of classical texts.

I personally maintain that the majority of Latin grammar can be explained orally and inductively, in order to then formalize and analyze it in depth in a manner that is largely traditional. To confirm this, I will allow myself a brief anecdote: about ten years ago, an eleven year-old boy named Josiah, who was totally unknown to me, wrote to me regarding his desire to learn Latin online in an active way. It had never occurred to me that you could teach and learn Latin via the Internet. Despite Josiah’s young age, I was curious and wanted to give it a try. I can confirm that, if you can judge a tree from its fruit, this endeavour had an excellent outcome, seeing as Josiah became the first American high school student to win a certamen in Italy, namely the Ovidianum in 2016. As far as I am concerned, what I learned from that experience, which resulted in a friendship, is the power of hearing Latin words in the teaching of the language. Josiah is a talented young man, but his mastery is owing to the method we used, as he himself recognizes. From the very first day I started teaching him Latin in Latin, accompanying the sounds not so much with actions (which is easier in a classroom) but with drawings and images that represented those sounds. In this way, we gradually arrived at reading classical texts fluently, but also at composing some poetry in Latin, which won him further plaudits in his home country.

It bears repeating that the goal was, and is, not to produce Latin writers, but if, from the very first day, one studies Latin for that which it is, a language, at a certain point it comes naturally not necessarily to compose Latin poetry, but to write good prose. There are also excellent examples of Italian students doing the same thing.

Therefore, I want to challenge teachers to imagine how they could explain Latin grammar, morphology and syntax, first in an active way (orally and inductively), and only then to formalize it in a concrete and traditional way. Latin cases, comparative and superlative forms, active and passive voice, verb tenses, indirect questions, cum and the subjunctive, etc., are all structures that can be illustrated in the manner we have shown above using the present indicative and imperative forms, as long as you use your imagination and, most importantly, a coherent method in accordance with our goal, which is not to learn Latin as a living language or as a second language, but to learn it as a language in which more than two millennia of literature has been written.

On the other hand, the Humanists had already had such an intuition regarding Latin teaching methods: the authors of many of the colloquia scholastica; or Comenius, with his Orbis pictus; and in the 1920s W. H. D. Rouse applied the direct method used in the teaching of living languages to ancient ones. In this regard, the following words seem meaningful to me (Rouse and Appleton, Latin on the direct method, 1925, p. 2; underlining mine):

As applied to the teaching of languages, the Direct Method means that the sounds of the foreign tongue are associated directly with a thing, or an act, or a thought, without the intervention of an English word and that these associations are grouped by a method, so as to make the learning of the language as easy and as speedy as possible, and are not brought in at haphazard, as they are when children learn their own language in the nursery. It follows that speaking precedes writing, and that the sentence (not the word) is the unit. The method is largely oral, but not wholly so: on the contrary, all the practices of indirect methods are used, but not at the same time, nor in the same proportion. Language is an art, and we proceed from art to science, from idiom to accuracy; the idiom, the feeling for a language, is easily taught thus, and accuracy can wait. To begin with an attempt at exactitude is to make idiom always difficult, and with mediocre minds, impossible to obtain in the end. It will be seen that four senses are used to make the impression: hearing first, then speech, then touch (when the new matter is written), and lastly sight. We may even enlist taste on occasion. The simpler the vocabulary, the easier it is to practise accidence and syntax: one thing is done at a time. The process is: first imitation, next imitation with a difference, lastly the use of what has been so learnt.

[This is the first part of the article; the second part can be read here.]

Roberto Carfagni

(Translated by Oscar Luca d’Amore and Jennifer K. Nelson.)

Leave A Comment